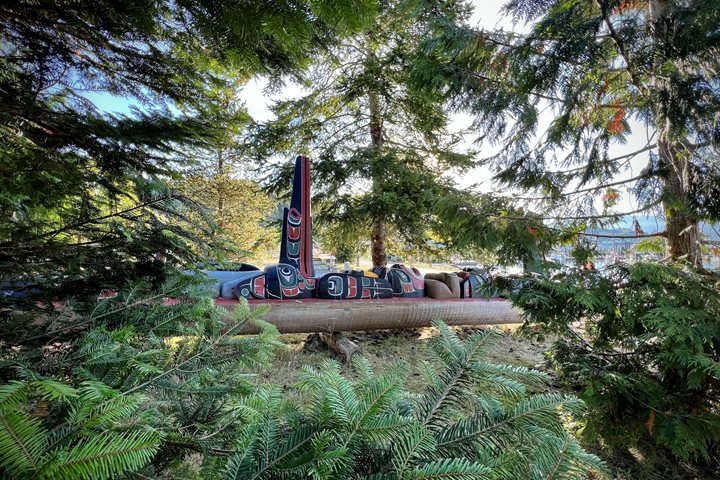

Spirit bear. Even the name conjures images of the supernatural: a ghost-colored black bear haunting the misty forest, a bridge between this world and the next. The native people of British Columbia’s Inside Passage recognized the sanctity of this sub-species. The bears were neither hunted nor spoken of, their protection vested in the secret of their existence.

There are between 100 to 500 spirit bears in the world, and the odds of viewing one on Princess Royal Island—one of the two most densely-populated spirit bear territories—peak at a mere 10%. It was with bated breath but subdued hopes that we scanned the fog-shrouded shoreline of the island as National Geographic Sea Lion cruised past, the sun having not long risen above the narrow channel. We had already passed Gribble Island, where spirit bear viewing odds are tripled, without success. The gray sky fell in shrouds about us and bald eagles stood watch over the downed logs lining an otherwise deserted coast.

National Geographic Sea Lion slowed down expectantly as we rounded a bend near an unnamed waterfall. Salmon flung their silver bodies upwards towards the river’s source. Then it happened: out of a cathedral of trees bordering the river on the right, a shimmering figure floated across the mosses into the water. The mists descended thickly upon it, white sky cloaking its white fur. The spirit bear nosed the falls, seeking the leaping salmon, then retreated into the forest on the far side of the river. Yet the mirage had not dissipated. The bear returned twice more along the shoreline, allowing us to bathe in its beautiful, ambling presence, perfectly at home in the Great Bear Rainforest lining one of Canada’s wildest coasts.

Our departure from the waterfall felt like a dream. Even the mists fell away as we cruised south, wrapping the land of the spirit bear in secrecy and allowing the sun to shine through on the small coastal communities lining our approach to Queen Charlotte Strait. Wild brethren continued to accompany us on our journey south as eagles soared lazily over the channel and porpoises played in the wake of our ship. As we entered the strait, the waters widened and dissipated behind a network of small, forested islands, beyond which the hazy mountains loomed.

A pair of traveling humpback whales joined us in the afternoon. One in particular remained close to the ship, its white pectoral fins glowing from beneath the sea as it swam placidly across our bow. The whoosh of a humpback whale breathing within a stone’s throw of the ship is not soon forgotten! Those of us aboard had the sad task of bidding our companion farewell to continue our journey, as the whale showed no signs of departing.

We travel to the wild places of our planet because we hold to a hope—stubborn and untamable—that we might experience their majesty and unravel some small part of their secrets for ourselves. Today, being so close to a near-mythic creature I had thought I might, someday, be lucky enough to glimpse, epitomized that allure of wilderness. We do what we do because the spirit bear still walks amidst the forests of British Columbia, because places like the Inside Passage hold secrets that we may yet be lucky enough to learn.